This essay was written for the book Between Affinity and Rupture: Tracing Bubbles, concerning the exhibition of the same name at the Bergsjön Cultural House in the fall of 2022. I am very grateful to MC Coble for making these fantastic drawings on the themes of my essay.

Seeds. Eggs. Amniotic sacs. The shell of a nut.

The most precious is protected, encased in a husk, a bubble.

I am precious. I protect myself, finding shelter inside that shell.

My bubble is a radical queer community, where people take care to treat each other with delicacy, understanding, patience. Eyes are friendly. They do not stare, rather they glow warmly when encountering a stranger who feels like family. My relationships are viewed as the precious fruits of a loving life, not as the perversions of a pathological mind.

I am much too frail to last long outside that sanctuary.

The open call for the exhibition framed the bubble mainly as social. Engaging with it, I feel a hegemonic impulse to also view it as problematic. There’s a familiar narrative: filter bubbles and echo chambers keep people apart, and what a healthy society needs is for people to spend as much time as possible with others who are different from them. This conflicts deeply with my urgent need for a protective sphere. A dilemma arises.

Perhaps I should make a work celebrating the virtues of the bubble. I don’t. The pull is too strong, the sense of duty toward the consensus-based democratic world view I’ve grown up on. My initial idea is to latch on to the social aspect of the theme, using my ongoing narrative project Underlevare. Through its fragmentary storytelling, Underlevare – a Swedish play on words relating to the concept of subsistence – documents the lives of a few people in a future Gothenburg, following a societal collapse.

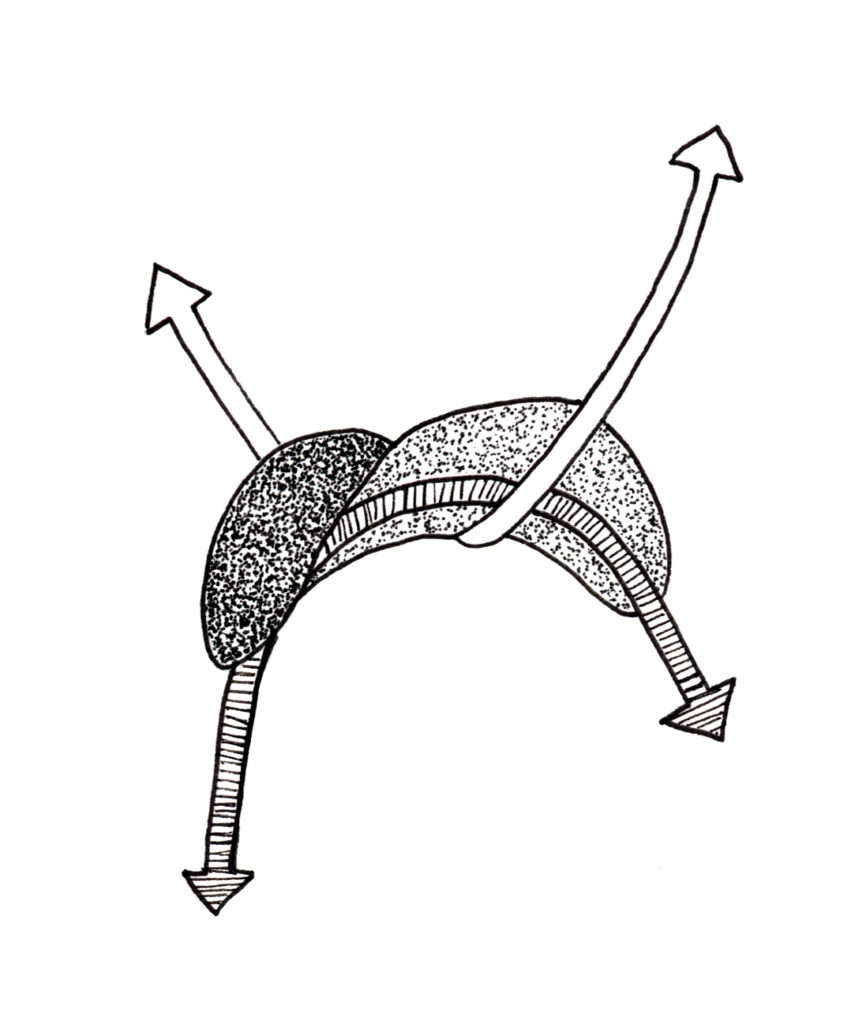

One of the main draws for me about the post-apocalyptic state is how it tends to be a fertile ground for the formation of little social islands – bubbles – where people can peacefully diverge from their neighbors: socially, spiritually, sexually. From the cults of Harry Martinson’s Aniara to the factions of open-world computer games like the Fallout series, there’s something liberating about a world that lacks a hegemonic culture to set limits on how far people are allowed to pursue their kookiness. For me, Underlevare has turned out to be one long sigh of relief at the demise of the status quo, the system that keeps us all pointed in a single direction, like obedient charges in society’s magnetic field. My contribution to the exhibition would then deal with how these post-apocalyptic bubbles eventually collide, as curiosity wins out over contempt and members of the various groups end up engaging in tentative dialogue.

I am, however, left with an uneasy feeling of inauthenticity. Like I’m running someone else’s errands, ticking the boxes required for fulfilling the role of Good Citizen. It doesn’t feel genuine, feels too simple, and it doesn’t have that sense of criticality, where something really is at stake. If a work lacks that, I can’t bear exposing it to the public. I need to go deeper.

Hearing the other artists talk about their interpretations of the curatorial theme, my curiosity is piqued by the bubble as a physical object. Those who know me wouldn’t be surprised: despite my love of metaphor, I certainly have a tendency to take things literally. What is it about soap bubbles that makes such a suggestive image? The bubble separates an inner from an outer. The inner is finite, and by convention small compared to the outer, which can in theory be infinite. This is how we differentiate Us from Them, subject from world.

The metaphor of the bubble tends to focus on the contained rather than that which contains. In the social reading, this might mean considering how life inside a subculture or oppressed demographic compares or relates to life in the normative mainstream of that society. What catches my attention, though, is the barrier between the two: the material doing the containing, the actual soap of the soap bubble.

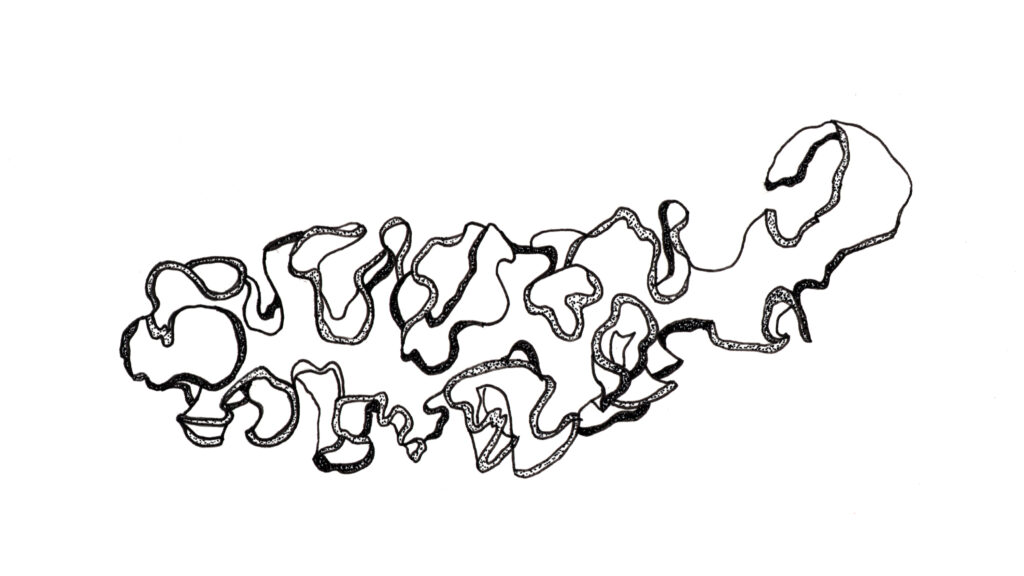

Under the laws of physics, this type of delimiting bubble inevitably takes on a very specific shape: the sphere. Feeling an obligation to stick with the bubble-critical program, I wonder what the mathematical anti-bubble would be? In geometry, the sphere is a two-dimensional shape of constant positive curvature, where any parallel lines eventually converge and collide. Its mathematical opposite is the hyperbolic plane, a surface of constant negative curvature. To me, a mathematics fangirl with great passion but no formal training, the hyperbolic has the air of a Bald Mountain, a mathematical twilight zone where anything can happen, where common sense is suspended.

I start researching, and a frenzied rush fills me: the excitement I feel when wrestling with a concept I don’t quite understand. I skim through Wikipedia articles about non-Euclidean geometry, struggle with academic papers way beyond my level. Is there a proof of the impossibility of emberdding a two-dimensional hyperbolic plane in three-dimensional flat space?

But beyond the intellectual fascination, there’s also something more. Is it ideology – can I seize on my love for the hyperbolic as a chance to act bubble-critical after all? Or is it a more private longing, deeper and more primal?

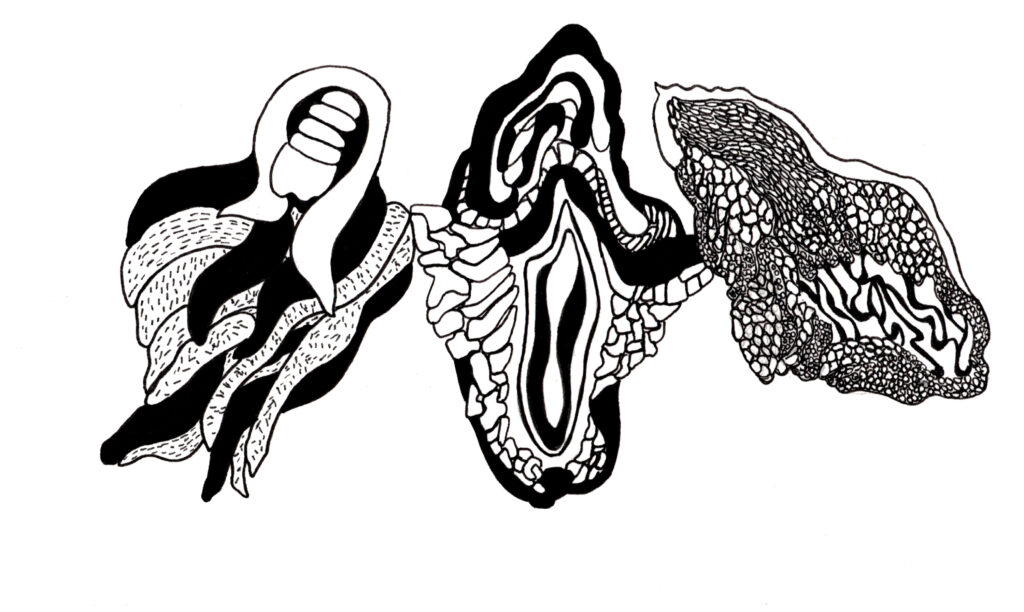

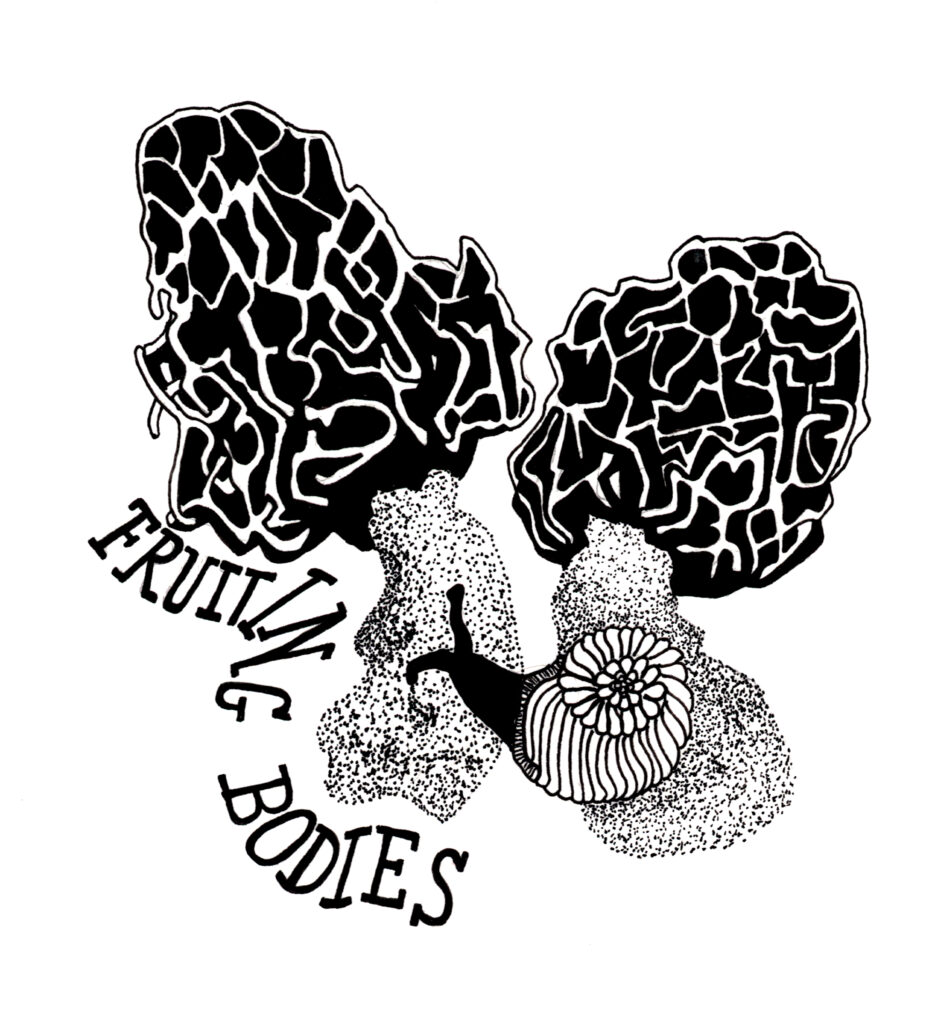

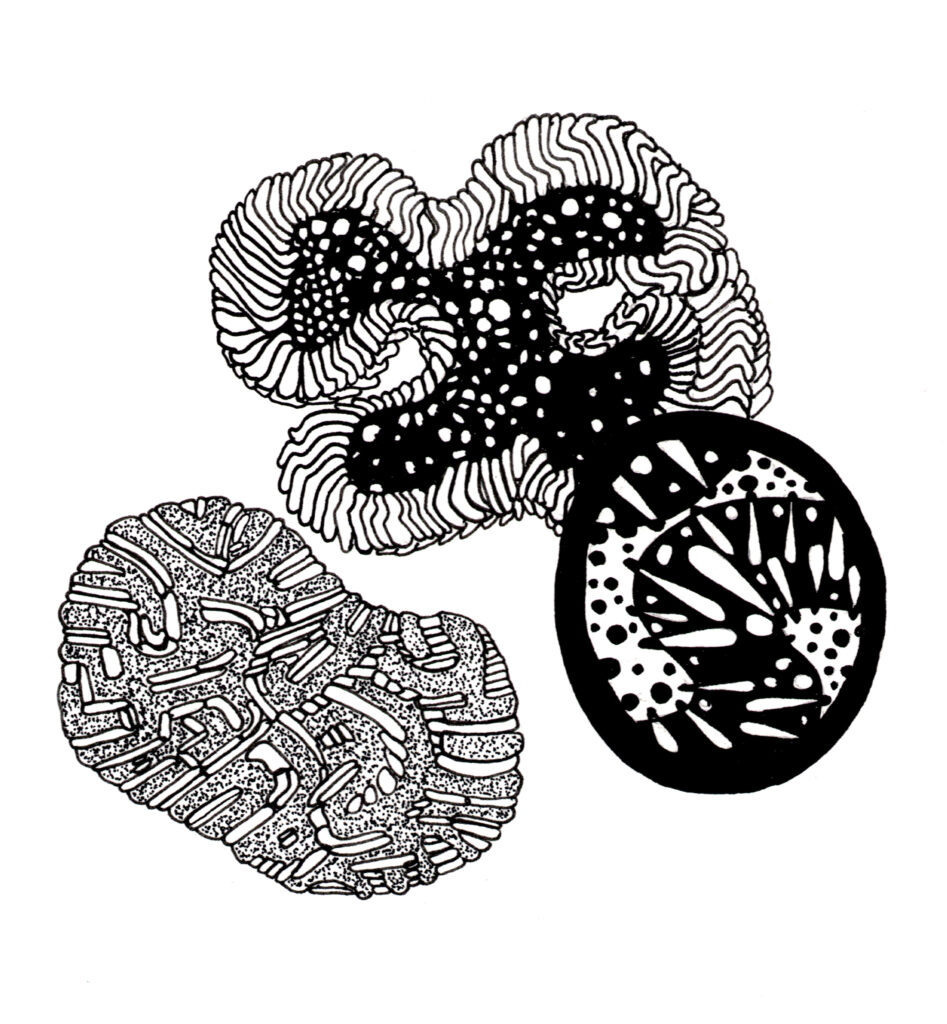

Googling for images, I spend hours letting my mind explore the flowing curves and endless expanses of shapes of negative curvature. Corals and morels. The brain’s cortex. Kale, kelp and holly. Foreskin and labia. It’s a giddy feeling, much like being in love. Days go by, and I get to a point where the mere thought of hyperbolic planes makes my skin come alive, ramping up its sensitivity as though preparing for intimate touch. And here is where something dawns on me.

For living things that grow hyperbolically, membranes aren’t about separation, as they are for nuts, eggs and bubbles. Rather, they are about contact. Negative curvature maximizes the surface area of any given volume, and these organisms are hungry for exposure to the surrounding air or water, supplying them with necessary nutrients.

In this geometry, exchange is made not through points but areas of contact – connectors of superior bandwidth. It is the intimacy of spoons rather than forks. No need for phallic protrusions because there is nothing to pierce, nothing to penetrate. Nothing is tucked away “inside” – there is nothing behind the surface. In physics, the holographic principle states that the information contained in any body can always fit on that body’s surface. Interiority is only a matter of perspective.

I gain confidence. This is familiar ground, this is where I belong. The state where separation is abolished: letting the boundaries of me and the boundaries of you become the boundary of us.

Dissolving together like bacteria in a Petri dish engaging in horizontal gene transfer, sharing and redistributing material in a constant state of change.

I meet a loved one – someone I often to refer to as “the third hemisphere of my brain” – for a bath in our local sauna. On most days, the sauna runs on a gendered policy, allowing either men or women to come and go as they like. I call these the “cisgender days”. Some weekdays, however, are reserved for private booking, and us trans people can have a go. Sealed off from the outside world – door securely locked behind us, phones left in the changing room – we enter into a state of incubation. In the heat, skin opens up to exchange fluids with its surroundings, and minds begin to meld as discussion takes off.

I raise the issue of the unspoken imperative for the dissolution of bubbles, from a society preaching the virtue of engaging with the Other. My friend frowns, pointing out that “leaving my bubble usually means I end up being the Other”. We wonder whether this insistence on dismantling community borders might in part be a product of hegemonic neoliberalism. Expecting that people can without consequence be extricated from their social circles, habits, customs and geographical attachments suggests a view of the individual as universal and perpetually moldable – a dream of capitalist ideology. For workers to be able to “flow freely” through global markets, we need to be generic in the same way that products have to be generic to become universably tradable commodities.

Leaving the sauna, I feel like I’ve internalized something about just how intertwined separation and connection are. Dissolution is dangerous without some sort of enclosing barrier to prevent us from being assimilated into the larger homogeneity, ending up as annoying but acceptable trace elements in the soup of a culture that would rather forget about our existence. Only inside a protective sphere can we afford to expose all of that skin, those surfaces of vulnerability and exchange.

I return to my Subsisters, bearing a new perspective on surface and containment, touch and separation. I engage the characters of Sara and Zinat in a dialogue about surface, skin and the virtues of shapes of different curvatures. The social perspective is there, but only as a background, as the dryly rational Sara continues her interactions with the previously ridiculed cult of the Ever-Renewed.

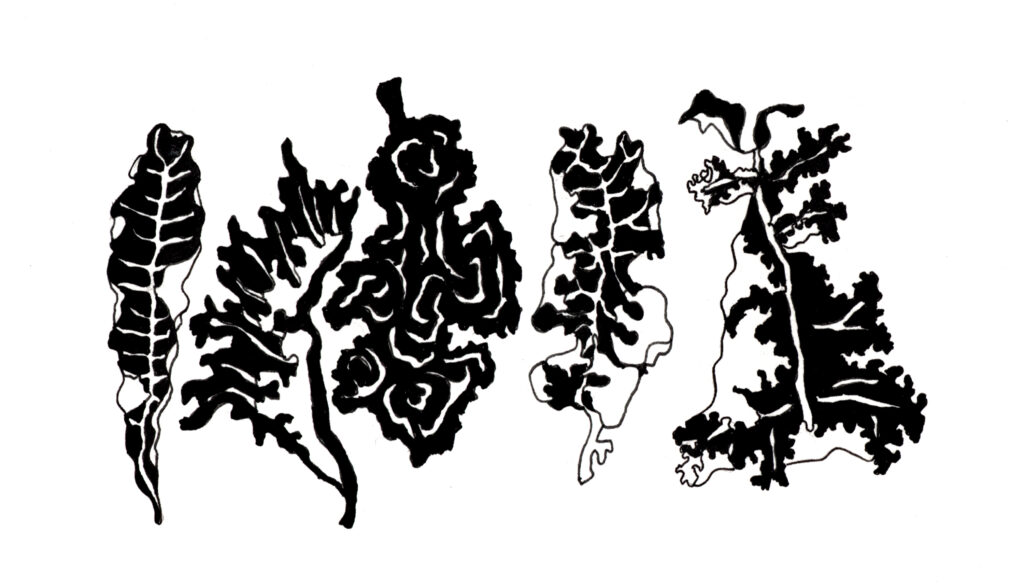

Keeping with my desire to anchor the theoretical in the material and visceral, I choose kale – with its negatively curved leaves – as the starting point for their discussion. Kale grows well in the Swedish climate, and Tracing Bubbles happens to take place during its harvest season. A friend offers me to pick some from her community garden; the kind you buy at the grocery store is flattened from being packed in a bag for a long time, losing much of the oomph of its inherent curvature. I include it in my installation as a mental stepping stone, a visual invitation to the world of the hyperbolic.

The process leaves me more grounded in my intuitive sense for the necessity of protection. And grateful to have so much skin with which to be naked.